Ent Schema

Ents (short for entity) are Convex documents, which allow explicitly declaring

edges (relationships) to other documents. The simplest ent has no fields besides

the built-in _id and _creationTime fields, and no declared edges. Ents can

contain all the same field types Convex documents can. Ents are stored in tables

in the Convex database.

Unlike bare documents, ents require a schema. Here's a minimal example of the

convex/schema.ts file using Ents:

import { v } from "convex/values";

import { defineEnt, defineEntSchema, getEntDefinitions } from "convex-ents";

const schema = defineEntSchema({

messages: defineEnt({

text: v.string(),

}).edge("user"),

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("messages", { ref: true }),

});

export default schema;

export const entDefinitions = getEntDefinitions(schema);Compared to a vanilla schema file (opens in a new tab):

defineEntSchemareplacesdefineSchemafromconvex/serverdefineEntreplacesdefineTablefromconvex/server- Besides exporting the

schema, which is used by Convex for schema validation, you also exportentDefinitions, which include the runtime information needed to enable retrieving Ents via edges and other features.

Fields

An Ent field is a field in its backing document. Some types of edges add additional fields not directly specified in the schema.

Ents add field configurations beyond vanilla Convex.

Indexed fields

defineEnt provides a shortcut for declaring a field and a simple index over

the field. Indexes allow efficient point and range lookups and efficient sorting

of the results by the indexed field. The following schema:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({}).field("email", v.string(), { index: true }),

});declares that "users" ents have one field, "email" of type string, and one

index called "email" over the "email" field. It is exactly equivalent to the

following schema:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

email: v.string(),

}).index("email", ["email"]),

});Unique fields

Similar to an indexed field, you can declare that a field must be unique in the table. This comes at a cost: On every write to the backing table, it must be checked for an existing document with the same field value. Every unique field is also an indexed field (as the index is used for an efficient lookup).

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({}).field("email", v.string(), { unique: true }),

});Field defaults

When evolving a schema, especially in production, the simplest way to modify the

shape of documents in the database is to add an optional field. Having an

optional field means that your code either always has to handle the "missing"

value case (the value is undefined), or you need to perform a careful

migration to backfill all the documents and set the field value.

Ents simplify this shape evolution by allowing to specify a default for a field. The following schema:

defineEntSchema({

posts: defineEnt({}).field(

"contentType",

v.union(v.literal("text"), v.literal("video")),

{ default: "text" },

),

});declares that "posts" ents have one required field "contentType",

containing a string, either "text" or "video". When the value is missing

from the backing document, the default value "text" is returned. Without

specifying the default value, the schema could look like:

defineEntSchema({

posts: defineEnt({

contentType: v.optional(v.union(v.literal("text"), v.literal("video"))),

}),

});but for this schema the contentType field missing must be handled by the code

reading the ent.

Adding fields to all union variants

If you use a union (opens in a new tab) as an ent's schema, you can add a field to all the variants:

defineEntSchema({

posts: defineEnt(

v.union(

v.object({

type: v.literal("text"),

content: v.string(),

}),

v.object({

type: v.literal("video"),

link: v.string(),

}),

),

).field("author", v.id("users")),

});adds an author field to both text and video posts.

Edges

An edge is a representation of some business logic modeled by the database. Some examples are:

- User A liking post X

- User B authoring post Y

- User C is friends with user D

- Folder F is a child of folder G

Every edge has two "ends", each being an ent. Those ents can be stored in the same or in 2 different tables. Edges can represent symmetrical relationships. The "friends with" edge is an example. If user C is friends with user D, then user D is friends with user C. Symmetrical edge only make sense if both ends of the edge point to Ents in the same table. Edges which are not symmetrical have two names, one for each direction. For the user liking a post example, one direction can be called "likedPosts" (from users to posts), the other "likers" (from posts to users).

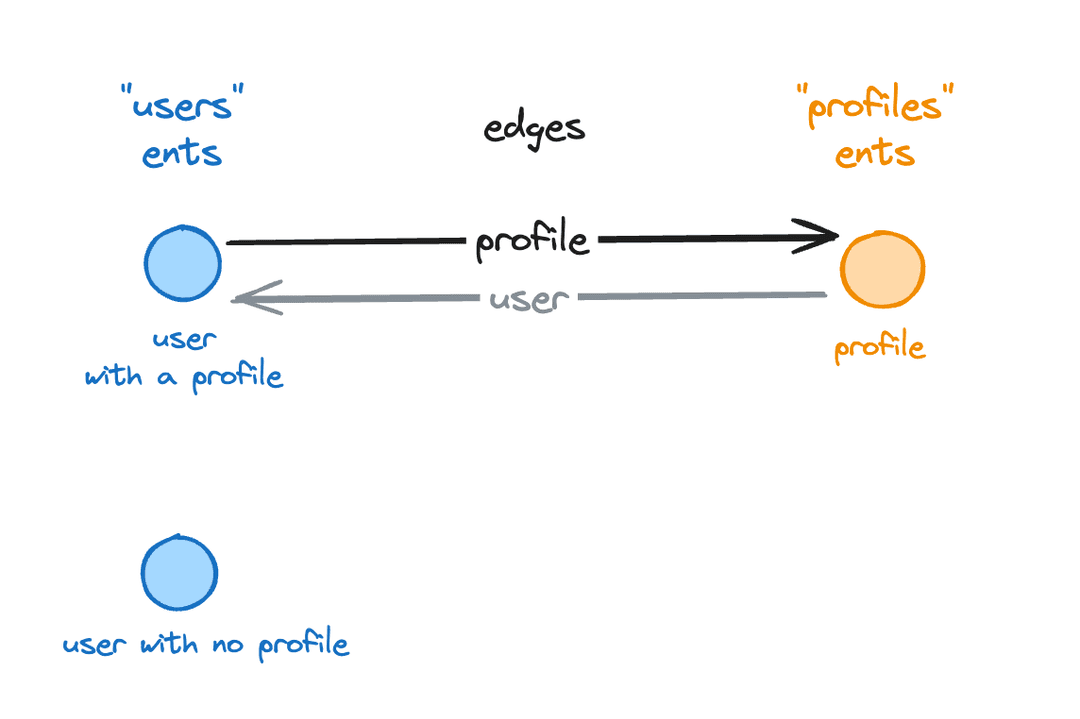

Edges can also declare how many ents can be connected through the same edge. For each end, there can be 0, 1 or many ents connected to the same ent on the other side of the edge. For example, a user (represented by an ent) has a profile (represented by an ent). In this case we call this a 1:1 edge. If we ask "how many profiles does a user X have?" the answer is always 1. Similarly there can be 1:many edges, such as a user with the messages they authored, when each message has only a single author; and many:many edges, such as messages to tags, where each message can have many tags, and each tag can be attached to many messages.

Now that you understand all the properties of edges, here's how you can declare them: Edges are always declared on the ents that constitute its ends. Let's take the example of users authoring messages:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("messages", { ref: true }),

messages: defineEnt({

text: v.string(),

}).edge("user"),

});In this example, the edge between "users" and "messages" is 1:many, each user can have many associated messages, but each message has only a single associated user. The syntax is explained below.

Understanding how edges are stored

To further understand the ways in which edges can be declared, we need to understand the difference in how they are stored. There are two ways edges are stored in the database:

- Field edges are stored as a single foreign key column in one of the two connected tables. All 1:1 and 1:many edges are field edges.

- Table edges are stored as documents in a separate table. All many:many edges are table edges.

In the example above the edge is stored as an Id<"users> on the "messages"

document.

1:1 edges

1:1 edges are in a way a special case of 1:many edges. In Convex, one end of the

edge must be optional, because there is no way to "allocate" IDs before

documents are created (see

circular references (opens in a new tab)).

Here's a basic example of a 1:1 edge, defined for each ent using the edge

(singular) method:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edge("profile", { ref: true }),

profiles: defineEnt({

bio: v.string(),

}).edge("user"),

});In this case, each user can have 1 profile, and each profile must have 1

associated user. This is a field edge stored on the "profiles" table as a

foreign key. The "users" table's documents do not store the edge, because the

ref: true option specifies that the edge a "refers" to the field on the other

end of the edge.

The syntax shown is actually a shortcut for the following declaration:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edge("profile", { to: "profiles", ref: "userId" }),

profiles: defineEnt({

bio: v.string(),

}).edge("user", { to: "users", field: "userId" }),

});The available options are:

tois the table storing ents on the other end of the edge. It defaults to edge name suffixed withs(edgeprofile-> table"profiles"). You'll want to specify it when this simple pluralization doesn't work (like edgecategoryand table"categories").refsignifies that the edge is stored in a field on the other ent. It can either be the literaltrue, or the actual field's name. You must specify the name when you want to have another field edge between the same pair of tables.fieldis the name of the field that stores the foreign key. It defaults to the edge name suffixed withId(edgeuser-> fielduserId).

The edge names are used when querying the edges, but they are not stored in the database (the field name is, as part of each document that stores its value).

Optional 1:1 edges

You can make the field storing the edge optional with the optional option.

Shortcut syntax:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edge("profile", { ref: true }),

profiles: defineEnt({

bio: v.string(),

}).edge("user", { field: "userId", optional: true }),

});You must specify the field name when using optional.

Fully specified:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edge("profile", { to: "profiles", ref: "userId" }),

profiles: defineEnt({

bio: v.string(),

}).edge("user", { to: "users", field: "userId", optional: true }),

});In this example a profile can be created without a set userId.

1:1 edges to system tables

You can connect ents to documents in system tables via 1:1 edges, see File Storage and Scheduled Functions for details.

1:many edges

1:many edges are very common, and map clearly to foreign keys. Take this

example, where the edge is defined via the edge (singular) and edges

(plural) method:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("messages", { ref: true }),

messages: defineEnt({

text: v.string(),

}).edge("user"),

});

This is a 1:many edge because the edges (plural) method is used on the "users"

ent and the ref: true option is specified. The ref option declares that the

edges are stored on a field in the other table. In this example each user can

have multiple associated messages.

The syntax shown is actually a shortcut for the following declaration:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("messages", { to: "messages", ref: "userId" }),

messages: defineEnt({

text: v.string(),

}).edge("user", { to: "users", field: "userId" }),

});The available options are:

tois the table storing ents on the other end of the edge.- for the

edgesmethod, it defaults to the edge name (edgesmessages-> table"messages") - for the

edgemethod, it defaults to the edge name suffixed withs(edgeuser-> table"users"). - You'll need to specify

towhen the defaults don't match your table names.

- for the

refsignifies that the edge is stored in a field on the other ent. It can either be the literaltrue, or the actual field's name. You must specify the name when you want to have another field edge between the same pair of tables (to identify the inverse edge).fieldis the name of the field that stores the foreign key. It defaults to the edge name suffixed withId(edgeuser-> fielduserId).

Optional 1:many edges

You can make the field storing the edge optional with the optional option.

Shortcut syntax:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("messages", { ref: true }),

messages: defineEnt({

text: v.string(),

}).edge("user", { field: "userId", optional: true }),

});You must specify the field name when using optional.

Fully specified:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("messages", { to: "messages", ref: "userId" }),

messages: defineEnt({

text: v.string(),

}).edge("user", { to: "users", field: "userId", optional: true }),

});In this case a message can be created without a set userId.

many:many edges

Many:many edges are always stored in a separate table, and both ends of the edge

use the edges (plural) method:

defineEntSchema({

messages: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("tags"),

tags: defineEnt({

text: v.string(),

}).edges("messages"),

});

In this case the table storing the edge is called messages_to_tags, based on

the tables storing each end of the edge.

The syntax shown is actually a shortcut for the following declaration:

defineEntSchema({

messages: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("tags", {

to: "tags",

table: "tags_to_messages",

field: "tagsId",

}),

tags: defineEnt({

text: v.string(),

}).edges("messages", {

to: "messages",

table: "tags_to_messages",

field: "messagesId",

}),

});The available options are:

tois the table storing ents on the other end of the edge. It defaults to the edge name (edgestags-> table"tags"). You can specify it if you want to call the edge something more specific.tableis the name of the table storing the edges. This table will have two ID fields, one for each end of the edge. You must specify the name when you want to have multiple different edges connecting the same pair of tables. These tables are only used by the framework under the hood, and won't appear in your code.fieldis the name of the field ontablethat stores the ID of the ent on this end of the edge. It defaults to the edge name with suffixed withId(edgetags-> fieldtagsId). These fields will only be used by the framework under the hood, and won't appear in your code.

Asymmetrical self-directed many:many edges

Self-directed edges have the ents on both ends of the edge stored in the same table.

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("followers", { to: "users", inverse: "followees" }),

});

Self-directed edges point to the same table on which they are defined via the

to option. For the edge to be asymmetrical, it has to specify the inverse

name. In this example, if this edge is between user A and user B, B is a

"followee" of A (is being followed by A), and A is a "follower" of B.

The table storing the edges is named after the edges, and so are its fields. You

can also specify the table, field and inverseField options to control how

the edge is stored and to allow multiple self-directed edges.

Symmetrical self-directed many:many edges

Symmetrical edges also have the ents on both ends of the edge stored in the same table, but additionally they "double-write" the edge for both directions:

defineEntSchema({

users: defineEnt({

name: v.string(),

}).edges("friends", { to: "users" }),

});

By not specifying the inverse name, you're declaring the edge as symmetrical.

You can also specify the table, field and inverseField options to control

how the edge is stored and to allow multiple symmetrical self-directed edges.

Other kinds of edges are possible, but less common.

Rules

Rules allow collocating the logic for when an ent can be created, read, updated or deleted.

See the Rules page.